Saturday, October 31, 2009

Oliver Masson as regards the ancient Macedonian Language

Thursday, October 22, 2009

The Yaunã takabara and the ancient Macedonians

by Demetrius E. Evangelides, Ethnologist

Recent research has provided unambiguous details concerning the ethnological classification of the ancient Macedonians, including from another source that lies outside the Greek world, which removes all doubt that had existed concerning the Hellenic nature of this nation. The unexpectedness of this source is certainly the fact that it comes from the Persian Empire – the Persians, the relentless enemies of the Greeks during antiquity.

North of the ruins of Persepolis, the capital of the Achaemenian Dynasty of the Persian Empire, at a distance of about 5 kilometers lies the site Naqsh-I Rustam (i.e. the reliefs of the [mythical hero] Rustam) where are to be found the tombs of Darius I (521-486 B.C.), his son Xerxes (486-465) and two more kings (Artaxerxes I and Darius II) cut into the rock, as well as eight other reliefs from the period of the Sassanids (the dynasty that ruled the Iranian plateau - after the Parthians - between 224 and 651 A.D. and is known for its wars against the Byzantines.

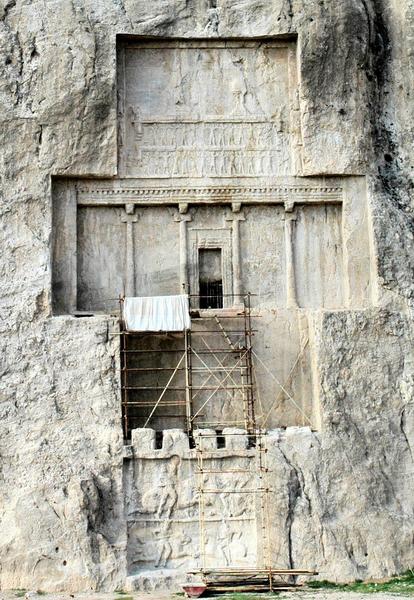

The Tomb of Darius at Naqsh-I Rustam

The façade of the tomb of Darius I has the shape of a cross (see the photograph) with the entrance to the tomb at the center, while above is a monumental relief showing Darius I who is praying at an altar of the supreme god of the Persians, Ohrmazd (Ahuramazda) on top of a base that is supported by 28 different subject peoples of the Persian Empire. An inscription at the upper right corner (see the photograph), known to archaeologists as DNa (i.e. Darius Naqsh [inscription] a), names those peoples, and presents Darius as a reverent and strong leader. Another inscription in the central part of the "cross", which consists of a representation of the southern entrance of the palaces of Persepolis, known as DNb, comprises the famous "Will" of Darius I, a copy of which is also – lightly adapted – on the façade of the tomb of Xerxes, known as XPl.

The inscription with the subject peoples (DNa)

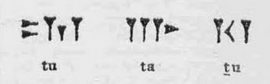

The text is written in the ancient Persian language (Old Persian) in a script inspired by the Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform script, but with simpler characters. As it has been maintained (see especially D.T. Potts: The Archaeology of Elam, 1999, p. 317) this first Persian script was created on purpose by Darius I for the texts of the famous inscription of Behistun. This script is syllabic consisting of only 36 symbols and also preserved four ideograms representing the words "King", "Country", "Province", and "Ahuramazda" (the supreme god in the Iranian Pantheon). The script was written from left to right, and is known as the "Syllabic System of Persepolis" (see image), and was used from the 6th to the 4th century B.C. for the monumental inscriptions of the Achaemenian Kings. After the kingship of Artaxerxes III (359/8-338 B.C.), inscriptions in the "Persepolis" script are completely lacking and after the dissolution of the Persian Empire by Alexander the Great, this script was not used again, given its connections with the previous regime (see Charles Higounet, Η γραφή Athens 1964, pp. 37-38).

The Syllabic System of Persepolis

In the aforementioned inscription DNa that lists the subject peoples, we read the following:

. . . King Darius says: By the favor of Ahuramazda these are the countries which I seized outside of Persia; I ruled over them; they bore tribute to me; they did what was said to them by me; they held my law firmly. (These countries are:) Media, Elam, Parthia, Areia, Baktria, Sogdia, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Arachosia, Sattagydia, Gandara, India, the Skythians who drink (the sacred drink) haoma, the Skythians with pointed caps, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, Armenia, Kappodokia, Lydia, the Ionians (Greeks of Asia Minor), the Skythians across the sea (on the shores of the Black Sea), Thrace, the Greeks who wear shieldlike headcoverings, the Libyans, the Nubians, the people of Maka and the Carians . . .

The Inscription on the tomb of Darius I (DNa)

In the above text, with the enumeration of the subject peoples we see that they include the Greek colonists of Asia Minor who are called in ancient Persian Yaunã (i.e. Ionians), a name for the Greeks that will subsequently be spread to all the peoples of the East. These Yaunã – Ionians (=Greeks) are referred to for the first time in a catalogue of subject peoples in the famous monumental inscription of Darius I at Behistun which we mentioned earlier (for details of the inscriptions see D. E. Evangelides, Λεξικό των Λαών του Αρχαίου Κόσμου, ΚΥΡΟΜΑΝΟΣ Thessaloniki 2006, under "Persians.")

But in the cited text in ancient Persian of Naqsh-I Rustam, some people described as Yaunã takabara (i.e. Greeks with shieldlike headcoverings) are mentioned. Who are these Greeks? We should mention that the inscription of Behistun is to be dated around 520 B.C. when Darius I swallowed the wave of rebellions which broke out during his ascension to the Persian throne and thus stabilized his power. In 513/2 B.C. Darius I undertook the well-known (thanks to Herodotus) "Skythian campaign” with which he took over Thrace (Skudra), the northern Greek region (i.e. Macedonia) and the regions around the mouth of the Danube where certain Skythian tribes lived (i.e. the across the sea Skythians).

It is thus determined that the mysterious Yaunã takabara or Greeks with shieldlike headcoverings were none other than the ancient Macedonians and the relevant facts of the submission by Amyntas I, father of Alexander I, are recorded by Herodotus (5.18-21).

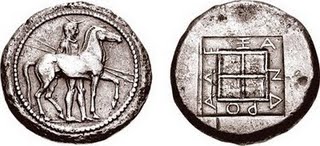

Thus for the Persians the Macedonians were Greeks (same language, same customs and same habits) and were therefore included within the Yaunã, but they separated from the other Greeks of Asia Minor, who were also subjects, because of the fact that they inhabited the European side of the Aegean and in order to distinguish them they were called after a characteristic, the type of head coverings they wore. We see that the same was done with the Skythians (Sakas in the Persian language) who are distinguished into those manufacturing / drinking the sacred drink haoma (Sakã haumavargã), nomads to the north of Sogdia and the Iaxartes River (=Syr Darya), and into those other Sakas (i.e. Skythians in Greek) who wore "pointy caps" (Sakã tigraxaudã) and live between the Caspian Sea and the Aral Sea, and finally into the Skythians who lived across the sea (Sakã tyaiy paradraya) whom the Persians encountered in the area at the mouth of the Danube. In addition, the Macedonians wore a characteristic headcovering called the kausia (Polybios 4.4-5, Arrian, Anabasis 7.22) that distinguished them from the rest of the Greeks. [The word kausia comes from the Greek root καύσ- from which καύση, καύσων =heat]. For that reason the Persians called them Yaunã takabara; i.e. "Greeks with shieldlike headcoverings." The Macedonian cap was very different form the headcovering that the Greeks of Asia Minor wore, and that detail was used by the Persians to distinguish between their Greek subjects.

Coin of Alexander I with a horseman wearing the Macedonian kausia.

The fact that completely proves the above analysis is that it comes also from a source foreign to the Greeks. In the inscription mentioned above from the Naqsh-I Rustam tomb of Xerxes, it is to be noted that in the catalogue of subject peoples there are missing the Yaunã takabara which agrees with everything we know from historical sources. After their failure to conquer Greece and after the battle of Plateia (479 B.C.) the Persians withdrew from their European holdings, and therefore from Macedonia. It was thus impossible at the time of the death of Xerxes (465 B.C.) to include the Yaunã takabara or Macedonians as subjects of the Persian Empire.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

MACEDONIA ARCHITECTURE Fragments ~ Large Art Print

The most representative examples of palace architecture in Greece are the palaces of Vergina (ancient Aigai) and Pella. The residential apartments of the palace at Vergina (350-325 BC) are disposed around a peristyle (central columned courtyard), while at Pella (mid-4th century BC) the ensemble consists of connected self-contained units forming suites around a peristyle and having access to a monumental gateway. Theaters, which often belonged to the same building project, were built near the palaces. At the time of the Successors and of the Antigonids, these building complexes underwent modifications and additions. In Thessalonike, the Galerian complex of the Roman period (early 4th century AD) is a unique example of combined royal residence, administrative-military center and Hippodrome. At that period new theaters (Dion) and odea were built and the older ones reconstructed in order to accommodate the contemporary requirements of theatrical performances and games.

The numerous sanctuaries of the Macedonian cities (Dion, Thessalonike, Pella, Amphipolis, Edessa) were either scattered about the city or concentrated in its religious center. The absence of their architectural remains is due to the lack of resistant building materials (such as marble) for the construction of monuments. In sanctuaries built of plastered limestone blocks and unbaked bricks, Zeus, Athena, Demeter, Dionysos, Artemis, Aphrodite, Asklepios, Herakles, and the Muses -- among others -- were worshipped under a variety of epithets. In the Hellenistic period the cult of various eastern deities, such as Serapis and Isis, was also introduced. To these divinities were added under the Romans the deified emperors (at Beroia, Thasos, Philippi). The cult of autochthonous gods was often combined with that of eastern deities in shrines containing small 'oikoi' (Dion, sacred precint of Isis).

BACKGROUND HISTORY ON PRINT : Louis XIV, the King of France, was a generous patron of the arts. During his long reign (1643-1715), he sought to raise standards of taste and sophistication in the Arts and so a number of royal academies were founded, including the Academy of Painting and Sculpture (1648), the Academie de France in Rome (1663) and the foundation of the Academie royale d'Architecture (1671). This formalized a system for the training of French architects and by elevating artisans to academicians, the power of the medieval guilds was eroded and centered instead on the patronage of the king. Subsidized by the state, the Academy of Architecture was free to those, aged fifteen to thirty, who could pass the entrance examinations. By the nineteenth century, students were obliged to complete a number of increasingly demanding concours or competitions, the most prestigious of which was the Grand Prix de Rome, a rigorous annual examination (a first competition was in 1702, then 1720, then yearly) that provided the winner advanced study at the French Academy in Rome at the Villa Medici, where classical antiquities could be seen first hand. Although drawings of ancient classical ornament had been made for generations before the winners of the Grand Prix de Rome were sent to the Villa Medici, these young French students were the first to go about the work systematically. The drawings were limited to, and solidly based on, carefully studied remains. Further, their presentation in formal academic renderings offers more information than could possibly be supplied even by a large number of photographs. Each year, for the four or five years they were in Rome, the students, supported financially with pensions, (hence their name of pensionnaires) were required to produce two sets of drawings, or envois, of Rome's ancient and medieval monuments: the état actuel, which was an exacting representation of the extant state, documenting the site with the precision of an archaeologist, and the état restauré, a more imaginary and often idealized restoration including the rendering of shade and shadow, which was accompanied by a written description of the monument's antiquity and construction. The artists progress usually was from a study of architectural ornaments and fragments gradually moving towards study and design of whole architectural ruins or sites. The series of prints presented here are those of the artist's earlier years when they focused on the details of architectural ornament.

The drawings submitted for the annual Grand Prix de Rome were on themes chosen by the Academy. The subjects set are indeed grand in scale and often in reach: triumphal arches (1730, 1747, 1763), palaces (1752, 1772, 1791, 1804, 1806), city squares and markets (1733, 1792, 1801), town halls (1742, 1787, 1813), law courts (1782, 1821) museums (1779) and educational institutions including libraries (1775, 1786, 1789, 1800, 1807, 1811, 1814, 1815, 1820) - all schemes for the promotion of civilization as the ancients would have understood the term. Stylistically, the entries usually share common characteristics: a grand Roman manner, with columns and orders, vaults and polychromy; an insistent and regular geometry, usually the square or the circle but sometimes the triangle; a penchant for the hemicycle, the propylaea and the pyramid; and finally a desire to impress by symmetry and the contrast between plain and decorated surfaces. These drawings first were shown in Rome at the French Academy and then were forwarded to Paris to be shown to the members of the Academie des Beaux Arts, one of the constituent bodies of the Institut de France, which was responsible for the Rome Academy. They were also exhibited to the public in Paris. Hector D'Espouy (1854-1929) won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1884, and after four years as a student at the Villa Medici, followed by several years of travel in Italy and Greece, as well as commissions for murals, he returned to the school that educated him in 1895 as the Professor of Ornamental Design at the Ecole Des Beaux Arts. It was in this role for the next several years that he amassed a large collection of the work of the students in Rome and the prints here are the best examples of this work.

Appreciation of these drawings cannot be complete without some explanation of the technique of India Ink wash rendering. Extreme discipline is required to produce these finely studied works of art. Even the simplest drawings require painstaking care and preparation before any of the washes are applied. Great skill is required to do the neccesary linework. All of the information must be recorded before tone is even thought about. The drawing is then meticulously transferred in ink to the watercolor paper and the paper mounted on a board. The rendering itself requires infinite care and patience. Each tone is built up through many faint layers of wash so that the ink seems to be in the paper rather than on it. Each surface is graded so that the final effect of the drawing is that of an object in light and space, with a sense of atmosphere surrounding it.

by Kostas K.

source: http://cgi.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewItem&category=360&item=280102952902

Monday, October 19, 2009

Sunday, October 18, 2009

ALEXANDER THE GREAT:Opening Up The World * Asia's Cultures in Transition

http://www.alexander-der-grosse-2009.de/

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Monday, October 05, 2009

Friday, October 02, 2009

German museum man says Alexander the Great was mainly Greek

The head of a German museum which is set to show an exhibition about Alexander the Great weighed into a dispute between Skopje and Athens on Friday, saying the ancient leader had been predominantly Greek.

The modern state of Macedonia, where the main language is a Slavic one, claims the heritage of ancient Macedonia.

'Alexander was predominantly Greek and definitely not an ancestor of contemporary Slavic Macedonians,' said Alfried Wieczorek, head of the Reiss-Engelhorn Museums in the southern German city of Mannheim.

The exhibition devoted to the ancient general and ruler, who lived from 356 to 323 BC, opens on Saturday and runs till February 21.

For two decades, Athens has been objecting to its northern neighbour calling itself Macedonia. Skopje has named its airport after Alexander and insists on having Alexander's 'star of Vergina' symbol on its coat of arms.

In an interview with the German Press Agency dpa, Wieczorek said, 'The latest research shows very clearly yet again that the Macedonians in the days of Alexander were closely related to the contemporary Greeks.'

He added, 'In antiquity, Greeks and Macedonians could interact because they spoke the same language.'

Athens has been insisting that the name Macedonia can only been applied to a province in its own north.

The country of Macedonia became independent in 1991 when Yugoslavia split up. The name issue has held up efforts to bring the new country into NATO and into formal assocation with the European Union.

The museum director referred to findings that its population of 2 million, one quarter of them Albanian speakers and three quarters Slavic speakers, are descended from people who immigrated in the 6th century of the modern era, long after Alexander's death.

http://www.monstersandcritics.com/news/europe/news/article_1504631.php/German-museum-man-says-Alexander-the-Great-was-mainly-Greek