By Miltiades Hatzopoulos, VI International Symposion on Ancient Macedonia, 1999.

http://macedonia-evidence.org/macedonian-tongue.html

Modern discussion of the speech of the ancient Macedonians began in 1808, when F. G. Sturz published a small book entitled De dialecto macedonica liber (Leipzig 1808), intended to be a scientific enquiry into the position of Macedonian within Greek. However, after the publication of O. Müller’s work Über die Wohnsitz, die Abstammung und die ältere Geschichte des makedonischen Volks (Berlin 1825), the discussion evolved into an acrimonious controversy -- initially scientific but soon political -- about the Greek or non-Greek nature of this tongue. Diverse theories were put forward:

I) Macedonian is a mixed language either of partly Illyrian origin -- such was the position of Müller himself, G. Kazaroff, M. Rostovtzeff, M. Budimir, H. Baric; or of partly Thracian origin, as it was maintained by D. Tzanoff.

II) Macedonian is a separate Indo-European language. This was the opinion of V. Pisani, I. Russu, G. Mihailov, P. Chantraine, I. Pudic, C. D. Buck, E. Schwyzer, V. Georgiev, W. W. Tarn and of O. Masson in his youth.

III) But according to most scholars Macedonian was a Greek dialect. This view has been expanded by F. G. Sturz, A. Fick, G. Hatzidakis, O. Hoffmann, F. Solmsen, V. Lesny, Andriotis, F. Geyer, N. G. L. Hammond, N. Kalleris, A. Toynbee, Ch. Edson and O. Masson in his mature years.

IV) Finally, a small number of scholars thought that the evidence available was not sufficient to form an opinion. Such was the view of A. Meillet and A. Momigliano.

Whatever the scientific merits of the above scholars, it was the nature of the evidence itself and, above all, its scarcity, which allowed the propounding of opinions so diverse and incompatible between themselves.

In fact, not one phrase of Macedonian, not one complete syntagm had come down to us in the literary tradition;

- because Macedonian, like many other Greek dialects, was never promoted to the dignity of a literary vehicle;

- because the Temenid kings, when they endowed their administration with a chancery worthy of the name, adopted the Attic koine, which in the middle of the fourth century was prevailing as the common administrative idiom around the shores of the Aegean basin.

Thus, the only available source for knowledge of Macedonian speech were the glosses, that is to say isolated words collected by lexicographers mainly from literary works because of their rarity or strangeness, and also personal names which, as we know, are formed from appellatives (Νικηφόρος< νίκη + φέρω).

The glosses, rare and strange words by definition, had the major defect of being liable to corruption, to alterations, in the course of transmission through the ages by copyists who could not recognise them.

As far as personal names are concerned, for want of scientific epigraphic corpora of the Macedonian regions, until very recently it was impossible to compile trustworthy lists.

On top of that, these two sources of information, far from leading to convergent conclusions, suggested conflicting orientations.

While the glosses included, besides words with a more or less clear Greek etymology (καρπαία· ὄρχησις μακεδονική [cf. καρπός]· κύνουπες· ἄρκτοι· Μακεδόνες [cf. κύνωψ]˙ ῥάματα· βοτρύδια, σταφυλίς· Μακεδόνες [cf. ῥάξ, gen. ῥαγός]), a significant number of terms hard to interpret as Greek ( γόδα˙ ἔντερα˙. Μακεδόνες; γοτάν˙ ὗν˙ Μακεδόνες; σκοῖδος˙ ἀρχή τις παρὰ Μακεδόσι [Hesychius]), the vast majority of personal names, not only were perfectly Greek (Φίλιππος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Παρμενίων, Ἀντίπατρος, Ἀντίοχος, Ἀρσινόη, Εὐρυδίκη) but also presented original traits excluding the possibility of their being borrowed from the Attic dialect, which was the official idiom of the kingdom (Ἀμύντας, Μαχάτας, Ἀλκέτας, Λάαγος), indeed from any other Greek dialect (Πτολεμαῖος, Κρατεύας, Βούπλαγος).

Until very recently it was hard to tell which set of evidence was more trustworthy.

During the last thirty years the situation has radically changed thanks to the publication of the epigraphic corpora of Thessalonike (1972) and Northern Macedonia (1999) by the Berlin Academy and of Upper Macedonia (1985) and Beroia (1998) by the Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity (KERA). Meanwhile the latter centre has also published three important onomastic collections: of Beroia, of Edessa and of Macedonians attested outside their homeland.

This intense epigraphic activity fed by continuous archaeological discoveries has brought to light an abundance of documents, among which the first texts written in Macedonian. This new body of evidence renders to a large extent irrelevant the old controversies and requires an ab initio re-opening of the discussion on a different basis.

Old theories however, die hard and relics of obsolete erudition still encumber handbooks and scientific journals. I particularly have in mind R. A. Crossland’s chapter in the second edition of volume III 1 of the Cambridge Ancient History and E. N. Borza’s latest booklet Before Alexander. Constructions of Early Macedonia published respectively in 1982 and 1999.

One reason – perhaps the main one – for such resistance to the assimilation of new evidence and persistence of obsolete theories until these very last years is the way in which since the nineteenth century the scholarly discussion about Macedonian speech and its Greek or non-Greek character has focused on the sporadic presence in Macedonian glosses and proper names -- which otherwise looked perfectly Greek -- of the sign of the voiced stop (β, δ, γ) instead of the corresponding unvoiced, originally “aspirated” stop expected in Greek, as for instance in Βάλακρος and Βερενίκα instead of Φάλακρος and Φερενίκα.

Here I must open a parenthesis. The traditional English pronunciation of classical Greek presents an obstacle to the understanding of the problem. To make things simple, one may say that classical Greek originally possessed several series of occlusive consonants or stops, that is to say consonants obtained by the momentary occlusion of the respiratory ducts. These, according to the articulatory region, can be distinguished into labials, dentals and velars (the occlusion is respectively performed by the lips, the teeth or the velum of the palate) and, according to the articulatory mode, into unvoiced (/p/, /t/, /k/), voiced (/b/, /d/, /g/) and unvoiced “aspirates” – in fact “expirates”, that is to say, accompanied by a breathing – (/ph/, /th/, /kh/). These “aspirates”, in some dialects from the archaic period and in most by the Hellenistic age, had become spirants, that is to say they were no longer obtained by the complete occlusion of the respiratory ducts, but by their simple contraction and were accordingly pronounced as /f/, /θ/, /χ/. At the same time the voiced stops also might, according to the phonetic context, lose their occlusion and become spirants pronounced /v/, /δ/, /γ/. In fact, the chronology of the passage from the “classical” to the “Hellenistic” pronunciation varied according to dialect and to region.

The occlusive consonants of Greek are the heirs of an Indo-European system which differed from the Greek one in that it possessed an additional series of occlusive consonants pronounced with both the lips and the velum. This series survived until the Mycenaean period, but was subsequently eliminated from all Greek dialects in various ways. Moreover, in the Indo-European system of consonants the place of the Greek series of unvoiced “aspirate” stops was occupied by a series of voiced “aspirate” stops, that is to say voiced stops accompanied by a breathing. These last ones (/bh/, /dh/, /gh/, gwh/) survived to a large extent only in Sanskrit and in modern Indian dialects. Elsewhere, they either lost their breathing (such is the case of the Slavonic, Germanic, and Celtic languages), or their sonority (such is the case of the Greek and Italic languages, in which they evolved into (/ph/, /th/, /kh/, /khw/). Thus the root bher- is represented by the verb bharami in Sanskrit, bero in Old Slavonic, baira in Gothic, berim in ancient Irish, φέρω in Greek and fero in Latin.

The supporters of the non-Greek nature of Macedonian reasoned as follows: if, instead of the well known Greek personal names Φάλακρος (“the bald one”) or Φερενίκη (“she who brings victory”) with a phi, we read the names Βάλακρος or Βερενίκα with a beta on the inscriptions of Macedonia, this is because the Macedonian tongue has not participated in the same consonant mutations as prehistoric Greek -- already before the first Mycenaean documents in Linear B -- which had transformed the “aspirate” voiced stops of Indo-European (/bh/, /dh/, /gh/) into “aspirate” unvoiced stops (/ph/, /th/, /kh/). That is to say that, instead of the loss of sonority of Greek, in Macedonian we are dealing with the loss of “aspiration” in Macedonian, which classifies the latter along with the Slavonic, the Germanic and the Celtic languages.

But, if Macedonian was separated from Greek before the second millennium B.C., it cannot be considered a Greek dialect, even an aberrant one.

What the partisans of such theories have not always explicitly stated is that they all rely on the postulate that the sounds rendered by the signs β, δ, γ in Macedonian glosses and proper names are the direct heirs of the series of voiced “aspirate” stops of Indo-European and do not result from a secondary sonorisation, within Greek, of the series represented by the signs φ, θ, χ. However,one must be wary of short-cuts and simplifications in linguistics. For instance, the sound /t/ in the German word “Mutter” is not the direct heir of the same sound in the Indo-European word *mater, but has evolved from the common Germanic form *moδer, which was the reflex of Indo-European *mater.

The example of Latin demonstrates that the evolution /bh/>/ph/>/f/>/v/>/b/, envisaged above, is perfectly possible. Thus, the form albus (“white”) in Latin does not come directly from Indo-European *albhos. In fact the stem albh- became first alph- and then alf- in Italic, and it was only secondarily that the resulting spirant sonorised into alv- which evolved into alb- in Latin (cf. alfu=albos in Umbrian and ἀλφούς˙ λευκούς in Greek). G. Hatzidakis (see especially Zur Abstammung der alten Makedonier [Athens 1897] 35-37) was the first – and for many years the only one – to stress the importance -- and at the same time the weakness -- of the implicit postulate of the partisans of the non-Greek character of Macedonian, to wit the alleged direct descent of the series represented by the signs of the voiced stops in the Macedonian glosses and personal names from the Indo-European series of “aspirate” voiced stops.

Since the middle of the eighties of the last century the acceleration of archaeological research in Macedonia and also the activities of the Macedonian Programme of the Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity (KERA) mentioned above have occasioned numerous scholarly works exploiting the new evidence has been collected and allows us to go beyond the Gordian knot which since the nineteenth century had kept captive all discussion about the tongue of the ancient Macedonians (Cl. Brixhe, Anna Panayotou, O. Masson, L. Dubois, M. B. Hatzopoulos). It would not be an exaggeration to say that henceforward the obstacle hindering the identification of the language spoken by Philip and Alexander has been removed: ancient Macedonian, as we shall see, was really and truly a Greek dialect. On this point all linguists or philologists actively dealing with the problem are of the same opinion. It is equally true that they do not agree on everything. Two questions still raise serious contention:

a) How should be explained this sporadic presence in Macedonian glosses and proper names of the signs of voiced stops (β, δ, γ) instead of the corresponding originally “aspirate” unvoiced ones (φ, θ, χ) of the other Greek dialects?

b) What is the dialectal position of Macedonian within Greek?

The first question has been tackled several times in recent years, but with divergent conclusions by Cl. Brixhe and Anna Panayotou on the one hand and O. Masson, L. Dubois and the present speaker on the other.

On the question of the dialectal affinities of Macedonian within Greek, besides the above mentioned scholars, N. G. L. Hammond and E. Voutiras have also made significant contributions. As far as I am concerned I have been gradually convinced that the two questions are intimately linked, or rather, that the search for the affinities of the Macedonian dialect can provide a satisfactory explanation of this controversial particularity of its consonantal system.

A problematic mutation

Down to very recent years discussion on the topic on the Macedonian consonantal system was almost exclusively dependent on literary evidence.

The systematic collection of inscriptions from Macedonia in the Epigraphic Archive of KERA occasioned the publication of three articles exploiting this epigraphic material, the first two in 1987 and the third in 1988.

The first one, written by the present speaker had its starting point in a series of manumissions by consecration to Artemis from the territory of Aigeai (modern Vergina), who was qualified as Διγαία and Βλαγαν(ε)ῖτις, the latter derived from the place name at which she was venerated (ἐν Βλαγάνοις).

It was obvious to me that the first epiclesis was nothing else than the local form of the adjective δίκαιος, δικαία, δίκαιον (“the just one”).

As for the explanation of the less obvious epiclesis Blaganitis and of the place name Blaganoi, the clue was provided by Hesychius’ gloss βλαχάν˙ ὁ βάτραχος, which I connected with one of the manumission texts qualifying Artemis as the godess [τῶν β]ατράχων.

The two epicleseis of Artemis demonstrated that Macedonian might occasionally present voiced consonants – in the case in hand represented by the letter gamma — not only instead of unvoiced “aspirates” (in this case represented by the letter chi of βλαχάν) but also instead of simple unvoiced stops (in this case represented by the letter kappa of Δικαία).

This discovery had important implications, because it showed that the phenomenon under examination, of which I collected numerous examples, had nothing to do with a consonant mutation going back to Indo-European, which could concern only the voiced “aspirates” and would make a separate language of Macedonian, different from the other Greek dialects. In fact, it ought to be interpreted as a secondary and relatively recent change within Greek, which had only partially run its course, as becomes apparent from the coexistence of forms with voiced as well as unvoiced consonants also in the case of the simple unvoiced stop (cf. Κλεοπάτρα-Γλευπάτρα, Βάλακρος-Βάλαγρος, Κερτίμμας-Κερδίμμας, Κυδίας-Γυδίας, Κραστωνία-Γραστωνία, Γορτυνία-Γορδυνία), but also from the presence of “hypercorrect” forms (cf. ὑπρισθῆναι=ὑβρισθῆναι, κλυκυτάτῃ=γλυκυτάτῃ, τάκρυν=δάκρυν).

This tendency to voice the unvoiced consonants was undoubtedly impeded after the introduction of Attic koine as the administrative language of the Macedonian state and only accidentally and sporadically left traces in the written records, especially in the case of local terms and proper names which had no correspondents and, consequently, no model in the official idiom.

In the second article published the same year I collected examples of forms with voiced and unvoiced sounds inherited from Indo-European voiced “aspirates” and was able to identify the complete series of feminine proper names with a voiced labial formed on the stem of φίλος: Βίλα, Βιλίστα, Βιλιστίχη parallel to Φίλα, Φιλίστα, Φιλιστίχη.

These names presenting a voiced consonant, rendered by a beta, formed according to the rules of Greek, and the Greek etymology of which was beyond doubt, convinced me that the explanation of the phenomenon should be sought within that language.

The third article, written jointly by Cl. Brixhe and Anna Panayotou, who was then preparing a thesis on the Greek language of the inscriptions found in Macedonia on the basis of the epigraphic documentation collected at KERA, followed another orientation.

– Whereas new evidence did not leave them in any doubt that the Macedonian of historical times spoken by Philip II and Alexander the Great was a Greek dialect, they contended that, besides this Macedonian, there had formerly existed another language in which the Indo-European “aspirates” had become voiced stops and that this language had provided the proper names and the appellatives presenting voiced stops instead of the unvoiced stops of Greek, for instance Βερενίκα and Βάλακρος instead of Φερενίκα and Φάλακρος.

These ideas were later developed and completed in a chapter devoted to Macedonian and published in a collective volume. In this paper Cl. Brixhe and Anna Panayotou identified this other language that according to them had disappeared before the end of the fifth century B.C., not before playing “a not insignificant part in the genesis of the Macedonian entity”, with the language of the Brygians or Phrygians of Europe.

Such was the beginning of a long controversy in the form of articles, communications to congresses and also private correspondence, which, as far as I am concerned, was particularly enriching, because it gave me the opportunity to refine my arguments.

Their objection, at first sight reasonable, to wit that a form such as Βερενίκα cannot be the product of the voicing of the first phoneme of Φερενίκα, for the “aspirate’ stop /ph/ has no voiced correspondent in Greek, obliged me to examine their postulate on the conservative character of the pronunciation of the consonants and, in a more general way, of the Attic koine spoken in Macedonia.

With the help of documents such as the deeds of sale from Amphipolis and the Chalkidike and of the boundary ordinance from Mygdonia, I was able to show that by the middle of the fourth century in Northern Greece

– the ancient “aspirate” stops written with the help of the signs φ,θ,χ had already lost their occlusion and had become spirants, that is to say they were formed by the simple contraction instead of the complete occlusion of the respiratory ducts;

– the ancient voiced stops written with the help of the signs β, δ, γ were pronounced, without any phonological significance, as spirants as well as stops, according to the phonetic context, just like in modern Castillian (ἄνδρες-πόδες; cf. andar-querido).

This contention is proved by “errors” such as βεφαίως in a mid-fourth century B.C. deed of sale from Amphipolis, which cannot be explained unless phi, pronounced like an f, indicated the unvoiced correspondent of the phoneme pronounced like a v and written with the help of the letter beta.

On the other hand, I drew attention to a series of allegedly “Brygian” terms – since they are found in Macedonian proper names presenting voiced consonants as reflexes of Indo-European voiced “aspirates” – which, however, showed a suspicious likeness with Greek words not only in their stems, but also in their derivation and composition. Thus, if we accept the Brygian theory, the name of the fifth Macedonian month Ξανδικός presupposes the existence of a Brygian adjectif xandos parallel to Greek ξανθός; likewise the Macedonian personal name Γαιτέας a Brygian substantive gaita (mane) parallel to Greek χαίτα (χαίτη); the Macedonian personal name Βουλομάγα a Brygian substantive maga parallel to Greek μάχα (μάχη); the Macedonian personal name Σταδμέας a Brygian substantive stadmos parallel to Greek σταθμός; the Macedonian personal names Βίλος, Βίλα, Βίλιστος, Βιλίστα a Brygian stem bil- parallel to Greek phil- and also Brygian rules of derivation identical to the Greek ones responsible for the formation of the superlative φίλιστος, φιλίστα (φιλίστη) and of the corresponding personal names Φίλιστος, Φιλίστα (Φιλίστη); the compound Macedonian personal names Βερενίκα and Βουλομάγα not only the Brygian substantives nika, bulon, maga and the verb bero parallel to Greek νίκα, φῦλον, μάχα, φέρω, but on top of that rules of composition identical to the Greek ones responsible for the formation of the corresponding Greek personal names Φερενίκα and Φυλομάχη.

However, the Brygian language reconstituted in this manner is not credible, for it looks suspiciously like Greek in disguise.

Finally, a series of observations 1) on the names of the Macedonian months, 2) on the use of the patronymic adjective, and 3) on a neglected piece of evidence for the Macedonian speech, induced me to reconsider the connexion between Macedonian and the Thessalian dialects.

1) The Macedonian calendar plays a significant role in the Brygian theory, because according to the latter’s supporters it testified the “undeniable cultural influence” of the Phrygian people in the formation of the Macedonian ethnos. They particularly refer to the months Audnaios, Xandikos, Gorpiaios and Hyperberetaios, which according to them can find no explanation in Greek.

– In fact, the different variants of the first month (Αὐδωναῖος, Αὐδυναῖος, Αὐδναῖος, Ἀϊδωναῖος) leave no doubt that the original form is ἈFιδωναῖος, which derives from the name of Hades, “the invisible” (a-wid-) and followed two different evolutions: on the one hand ἈFιδωναῖος>Αὐδωναῖος>Αὐδυναῖος>Αὐδναῖος, with the disappearence of the closed vowel /i/ and the vocalisation of the semi-vowel /w/ and, later, with the closing of the long vowel /o:/ into /u/ (written –υ-) and finally with the disappearence of this closed vowel, and, on the other hand ἈFιδωναῖος> Ἀϊδωναῖος, with the simple loss of intervocalic /w/.

– The case of Xandikos is even clearer. It was felt as a simple dialectal variant within the Greek language, as is apparent from the form Ξανθικός attested both in literary texts and in inscriptions.

– Concerning Γορπιαῖος, Hofmann had already realised that it should be connected with καρπός, the word for fruit in Greek, which makes good sense for a month corresponding roughly to August (cf. the revolutionary month Fructidor). This intuition is confirmed today, on the one hand by the cult of Dionysos Κάρπιος attested in neighbouring Thessaly and, on the other hand, by the variant Γαρπιαῖος showing that we are dealing with a sonorisation of the unvoiced initial consonant, a banal phenomenon in Macedonia, and a double treatment of the semi-vowel /r/, of which there are other examples from both Macedonia and Thessaly.

– The name of the twelfth month Ὑπερβερεταῖος, the Greek etymology of which was put in doubt, orientates us too in the direction of Thessaly. In fact it is inseparable from the cult of Zeus Περφερέτας also attested in nearby Thessaly.

2) At the exhibition organised at Thessalonike in 1997 and entitled Ἐπιγραφὲς τῆς Μακεδονίας was presented an elegant funerary monument from the territory of Thessalonike of the first half of the third century B.C. bearing the inscription Πισταρέτα Θρασίππεια κόρα.

– Κόρα as a dialectal form of Attic κόρη is also known from other inscriptions found in Macedonia. As for the use of the patronymic adjective instead of the genitive as a mark of filiation (Ἀλέξανδρος Φιλίππειος instead of Ἀλέξανδρος Φιλίππου), which is characteristic of Thessalian and more generally of the "Aeolic" dialects, it had been postulated by O. Hoffmann on the basis of names of cities founded by the Macedonians, such as Ἀλεξάνδρεια, Ἀντιγόνεια, Ἀντιόχεια, Σελεύκεια. Now it was for the first time directly attested in a text which could be qualified as dialectal.

– The confirmation that the patronymic adjective constitutes a local Macedonian characteristic and that the monument of Pistareta could not be dismissed as set up by some immigrant Thessalians was provided by a third century B.C. manumission from Beroia, which, although written in Attic koine,refers to the daughter of a certain Agelaos as τὴν θυγατέρα τὴν Ἀγελαείαν.

3) Finally, although it had been known for centuries, recent studies have ignored the sole direct attestation of Macedonian speech preserved in an ancient author. It is a verse in a non-Attic dialect that the fourth century Athenian poet Strattis in his comedy The Macedonians (Athen. VII, 323b) puts in the mouth of a character, presumably Macedonian, as an answer to the question of an Athenian ἡ σφύραινα δ’ἐστὶ τίς; (“The sphyraena, what’s that?”): κέστραν μὲν ὔμμες, ὡτικκοί, κικλήσκετε (“It’s what ye in Attica dub cestra”).

Thus research on the Macedonian consonantal system has led to the question of the dialectal affinities of this speech, to which it is closely connected.

It was natural that the major controversy about the Greek or non-Greek character of Macedonian had relegated to a secondary position the question of its position within the Greek dialects. Nevertheless it had not suppressed it completely.

Already F. G. Sturz, following Herodotos, considered Macedonian a Doric dialect, whereas O. Abel was even more precise and placed it among the northern Doric dialects. He thought that Strabo and Plutarch provided the necessary arguments for maintaining that Macedonian did not differ from Epirote.

It was the fundamental work of O. Hoffmann that forcibly introduced the Aeolic thesis into the discussion, which is largely accepted in our days (Daskalakis, Toynbee, Goukowsky).

The Doric-north-western thesis made a strong come-back thanks to the authority of J. N. Kalleris followed by G. Babiniotis, O. Masson and other scholars with more delicately shaded opinions (A. Tsopanakis, A. I. Thavoris, M. B. Sakellariou and Brixhe).

Finally, N. G. L. Hammond held a more original position, arguing for the parallel existence of two Macedonian dialects: one in Upper Macedonia close to the north-western dialects and another in Lower Macedonia close to Thessalian.

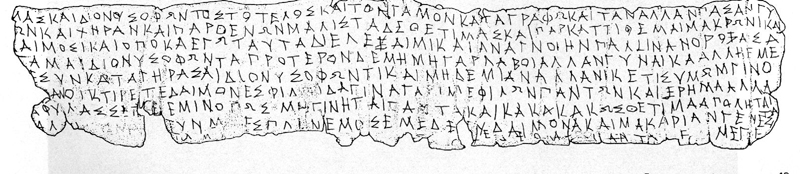

But a new piece of evidence, the publication of a lengthy dialectal text from Macedonia, created a new situation. It is a curse tablet from Pella dating from the first half of the fourth century B.C. which was discovered in a grave at Pella.

[Θετί]μας καὶ Διονυσοφῶντος τὸ τέλος καὶ τὸν γάμον καταγράφω καὶ τᾶν ἀλλᾶν πασᾶν γυ-

[ναικ]ῶν καὶ χηρᾶν καὶ παρθένων, μάλιστα δὲ Θετίμας, καὶ παρκαττίθεμαι Μάκρωνι καὶ

[τοῖς] δαίμοσι· καὶ ὁπόκα ἐγὼ ταῦτα διελέξαιμι καὶ ἀναγνοίην πάλειν ἀνορόξασα,

[τόκα] γᾶμαι Διονυσοφῶντα, πρότερον δὲ μή· μὴ γὰρ λάβοι ἄλλαν γυναῖκα ἀλλ’ ἢ ἐμέ,

[ἐμὲ δ]ὲ συνκαταγηρᾶσαι Διονυσοφῶντι καὶ μηδεμίαν ἄλλαν. Ἱκέτις ὑμῶ(ν) γίνο-

[μαι· Φίλ?]αν οἰκτίρετε, δαίμονες φίλ[ο]ι, δαπινὰ γάρ

ἰμε φίλων πάντων καὶ ἐρήμα· ἀλλὰ

[ταῦτ]α φυλάσσετε ἐμὶν ὅπως μὴ γίνηται τα[ῦ]τα καὶ

κακὰ κακῶς Θετίμα ἀπόληται.

[----]ΑΛ[----]ΥΝΜ..ΕΣΠΛΗΝ ἐμός, ἐμὲ δὲ [ε]ὐ[δ]αίμονα καὶ μακαρίαν γενέσται

[-----] ΤΟ[.].[----].[..]..Ε.Ε.ΕΩ[ ]Α.[.]Ε..ΜΕΓΕ[---]

“Of Thetima and Dinysophon the ritual wedding and the marriage I bind by a written spell, as well as (the marriage) of all other women (to him), both widows and maidens, but above all of Thetima; and I entrust (this spell) to Macron and the daimones. And were I ever to unfold and read these words again after digging (the tablet) up, only then should Dionysophon marry, not before; may he indeed not take another woman than myself, but let me alone grow old by the side of Dionysophon and no one else. I implore you: have pity for [Phila?], dear daimones, for I am indeed downcast and bereft of friends. But please keep this (piece of writing) for my sake so that these events do not happen and wretched Thetima perishes miserably. [---] but let me become happy and blessed. [---]” (translation by E. Voutiras, modified).

E. Voutiras, the editor of the tablet from Pella, was well aware of the linguistic traits that his text shared with the north-western Greek dialects: in particular the conservation of the long /a/ (or of its reflex: ἄλλαν), the contraction of /a/ and /o/ (short or long) into a long /a/ (or its reflex: ἀλλᾶν), the dative of the first person singular of the personal pronoun ἐμίν, the presence of temporal adverbs ending in –κα (ὁπόκα), the apocope of verbal prefixes (παρκαττίθεμαι), the dissimilation of consecutive spirants which betrays the use of the signs -στ- instead of -σθ-; but, on the other hand, he ignored, as if they were simple errors, the dialectal traits which did not conform to the purely north-western idea that he had of the dialect. These, as L. Dubois and I have pointed out, are in particular the forms διελέξαιμι, ἰμέ, ἀνορόξασα, δαπινά instead of διελίξαιμι, εἰμί, ἀνορύξασα, ταπεινά, which bear witness to phonetic phenomena having, in the first three cases, their correspondents both in dialectal Thessalian texts and in koine texts from Macedonia, whereas the fourth case presents the voicing of the unvoiced typical of the Macedonian dialect.

Cl. Brixhe returned to this text with a thorough analysis which confirmed and refined those of his predecessors. He pointed out the treatment of the group –sm-, with the elimination of the sibilant and the compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel, which is proper to north-western dialects but not Thessalian, the presence of the particle –κα, expected in the north-western dialects as opposed to Thessalian –κε, and the athematic form of the dative plural δαίμοσι, attested in the north-western dialects but not in Thessalian, where one would expect δαιμόνεσσι; he interpreted the graphic hesitation Ε/Ι, Ο/Υ (pronounced /u/) as resulting “from a tendency, in the Macedonian dialect and, later, in the koine of the region towards a closing of the vocales mediae e and o, respectively becoming i and u”, which indicated an affinity of Macedonian not with the north-western dialects but with Attic and even more with Boeotian and Thessalian and with the northern dialects of modern Greek; he adopted L. Dubois’ interpretation of δαπινά and admitted that the spirantisation of the “aspirates” and the voiced stops in Macedonian had already taken place in the classical period, but persisted in considering “more efficient” his interpretation of forms such as Βερενίκα as “Brygian” rather than Greek.

In my opinion the presence of forms such as διελέξαιμι, ἰμέ, ἀνορόξασα, δαπινά, expected in Macedonia but alien to the north-western dialects, is a decisive confirmation of the local origin of the author of the text and allows the elimination of the unlikely hypothesis that it might have been the work of an Epirote resident alien living in Pella. But this is not all. The fact that the closing of the vocales mediae, of which the first three examples bear witness, is a phenomenon well attested in Thessalian confirms the coexistence of north-western and of Thessalian characteristics in Macedonian; it indicates the intermediate position of the latter dialect, and legitimises the attempt to verify whether the tendency to voice the unvoiced consonants was not shared with at least some Thessalian dialects.

Kalleris had already pointed out that the place names Βοίβη and Βοιβηίς and the personal names Δρεβέλαος and Βερέκκας, which were attested in Thessaly but were unknown in Macedonia, respectively corresponded to Φοίβη, Φοιβηίς, Τρεφέλεως and to a composite name, the first element of which was Φερε-. Nevertheless he did not draw the conclusion that the sonorisation phenomenon, far from being limited to Macedonia, was common to that area and to Thessaly, because he refused to admit its localisation in Macedonia and in nearby areas, as P. Kretschmer had suggested.

In previous papers I had added to these place names a third one, Ὀττώλοβος (Ὀκτώλοφος), and a series of personal names either unknown (then) in Macedonia: Βουλονόα (Φυλονόα) or attested in a different form: Σταδμείας (Σταθμείας), Παντορδάνας (Παντορθάνας). The publication of fascicule III.B of the Lexicon of Greek Personal Names, which contains the onomastic material from Thessaly makes it now possible to add additional examples: Ἀμβίλογος, Βύλιππος, Βῦλος corresponding to Ἀμφίλοχος, Φύλιππος, Φῦλος, in the same manner that Βουλομάγα and Βουλονόα correspond to Φυλομάχη and Φυλονόη. Moreover, the frequent attestation of Κέββας in Thessaly does not allow us to consider it as an onomastic loan from Macedonia, where this personal name is attested only once.

Is it now possible to separate this hypocoristic from the family of personal names well represented in Thessaly and derived from the Greek appellative κεφαλή, one of which, namely Κεφαλῖνος, appears in Macedonia as Κεβαλῖνος? And if the purely Thessalian Ἀμβίλογος, Βύλιππος, Βῦλος, Βερέκκας or the both Thessalian and Macedonian Βουλομάγα, Βουλονόα, Κέββας find a perfect explication in Greek, what need is there to solicit the Phrygian language in order to explain the Macedonian form Βερενίκα, which is attested in Thessaly as Φερενίκα, since its case is strictly analogous to that of Κεβαλῖνος/Κεφαλῖνος?

If we now consider the geographic distribution of the forms with voiced consonants in Thessaly, we observe that they are concentrated in the northern part of the country, essentially in Pelasgiotis and Perrhaibia, with the greater concentration in the latter region. But in Macedonia also these forms are unequally distributed. They are to be found in significant numbers and variety – bearing witness to the authentic vitality of the phenomenon – in three cities or regions: Aigeai, Beroia and Pieria. Now all these three are situated in the extreme south-east of the country, in direct contact with Perrhaibia. I think that this geographical distribution provides the solution to the problem. We are dealing with a phonetic particularity of the Greek dialect spoken on either side of Mount Olympus, undoubtedly due to a substratum or an adstratum, possibly but not necessarily, Phrygian. If there remained any doubts regarding the Greek origin of the phenomenon, two personal names: Κεβαλῖνος and Βέτταλος should dispel it. It is well known that the first comes from the Indo-European stem *ghebh(e)l-. If, according to the “Brygian” hypothesis, the loss of sonority of the “aspirates” had not taken place before the dissimilation of the breathings, the form that the Greek dialect of Macedonia would have inherited would have been Γεβαλῖνος and not Κεβαλῖνος, which is the result first of the loss of sonority of the “aspirates’ and then of their dissimilation. Cl. Brixhe and Anna Panayotou, fully aware of the problem, elude it by supposing a “faux dialectisme”. Βέτταλος, on the other hand, is obviously a Macedonian form of the ethnic Θετταλός used as a personal name with a probable transfer of the accent. We also know that the opposition between Attic Θετταλός and Boeotian Φετταλός requires an initial *gwhe-. Given, on the one hand, that in Phrygian, contrary to Greek, the Indo-European labiovelars lost their velar appendix without conserving any trace thereof, the form that the Greek dialect of Macedonia should have inherited according to the “Brygian” hypothesis would have an initial *Γε-, which manifestly is not the case. On the other hand, the form Βέτταλος, which the Macedonians pronounced with a voiced initial consonant, is to be explained by a form of the continental Aeolic dialects, in which, as we know, the “aspirate” labio-velars followed by an /i/or an /e/ became simple voiced labials. The Aeolic form Φετταλός, lying behind Βετταλός, provides us with a terminus post quem for the voicing phenomenon. For, if we take into consideration the spelling of the Mycenaean tablets, which still preserve a distinct series of signs for the labiovelars, it is necessary to date this phenomenon at a post-Mycenaean period, well after the elimination of the labio-velars, that is to say at the end of the second millennium B.C. at the earliest, and obviously within the Greek world. It is manifest that in the case of Βέτταλος an ad hoc hypothesis of a “faux dialectisme” is inadmissible, for at the late date at which a hypothetical Macedonian patriot might have been tempted to resort to such a form the Thessalian ethnic had long since been replaced by the Attic koine form Θετταλός. Its remodelling into a more “Macedonian-sounding” Βετταλός would have demanded a level of linguistic scholarship attained only in the nineteenth century A.D.

Historical Interpretation

According to Macedonian tradition the original nucleus of the Temenid kingdom was the principality of Lebaia, whence, after crossing Illyria and Upper Macedonia, issued the three Argive brothers , Gauanes, Aeropos and Perdikkas, as they moved to conquer first the region of Beroia, then Aigeai and finally the rest of Macedonia.

It is highly probable that the royal Argive ancestry was a legend invented in order to create a distance and a hierarchy between common Macedonians and a foreign dynasty allegedly of divine descent. Might this legend nevetheless not retain, some authentic historical reminiscence?

In a previous paper, first read at Oxford some years ago, I attempted to show that Lebaia was a real place in the middle Haliakmon valley near the modern town of Velvendos, a region the economy of which was until very recently based on transhumant pastoralism. It is a likely hypothesis that during the Geometric and the Archaic period too the inhabitants of this region made their living tending their flocks between the mountain masses of Olympus and the Pierians and the plains of Thessaly, Pieria and Emathia, until under a new dynasty they took the decisive step of permanently settling on the fringe of the great Macedonian plain, at Aigeai.

What were the ethnic affinities of these transhumant shepherds? A fragment of the Hesiodic catalogue preserves a tradition according to which Makedon and Magnes were the sons of Zeus and of Thyia, Deukalion’s daughter, and lived around Pieria and Mount Olympus. The Magnetes, of whom Magnes was the eponymous hero, were one of the two major perioikic ethne of northern Thessaly, who originally spoke an Aeolic dialect.

The other one was the Perrhaibians. Although they were not mentioned in the Hesiodic fragment, we know by Strabo that even at a much later period they continued to practice transhumant pastoralism. Their close affinity with the Macedonians is evident not only from onomastic data, but also from their calendar. Half of the Perrhaibian months the names of which we know figure also in the Macedonian calendar. Thus, it is no coincidence that Hellenikos presents Makedon as the son of Aiolos.

The above data outline a vast area between the middle Peneios and the middle Haliakmon valleys, which in prehistoric times was haunted by groups of transhumant pastoralists who spoke closely related Greek dialects. Is it unreasonable to think that, just as in modern times the Vlachs of Vlacholivado, who frequented precisely the same regions, spoke, under the influence of the Greek adstratum, a peculiar neo-Latin dialect, their prehistoric predecessors had done the same (undoubtedly under the influence of another adstratum which remains to be defined) and that the tendency to voice the unvoiced consonants was one of these peculiarities?

As to the three Temenid brothers, according to Herodotos mythical founders of the Macedonian kingdom, already in antiquity there was a suspicion that they had not come from Peloponnesian Argos but from Argos Orestikon in Upper Macedonia, hence the name Argeadai given not only to the reigning dynasty but to the whole clan which had followed the three brothers in the adventure of the conquest of Lower Macedonia. Knowing that the Orestai belonged to the Molossian group, it is readily understandable how the prestigious elite of the new kingdom imposed its speech, and relegated to the status of a substratum patois the old Aeolic dialect, some traits of which, such as the tendency of closing the vocales mediae and the voicing of unvoiced consonants survived only in the form of traces, generally repressed, with the exception of certain place names, personal names and month names consecrated by tradition.

Select Bibliography

G. Babiniotis, “ Ancient Macedonia : the Place of Macedonian among the Greek Dialects “, Glossologia 7-8 (1988-1989) 53-69.

- “ The Question of Mediae in Ancient Macedonian Greek Reconsidered “, Historical Philology : Greek, Latin and Romance (“ Current Issues in Linguistic Theory ” 87; Amsterdam-Philadelphia 1992) 30-33.

Cl. Brixhe, “ Un nouveau champ de la dialectologie grecque : le macédonien “, KATA DIALEKTON, Atti del III Colloquio Internqzionale di Dialettologia Greca. A.I.O.N. 19 (1997) 41-71.

Cl. Brixhe - Anna Panayotou, “ L’atticisation de la Macédoine : l’une des sources de la koinè “, Verbum 11 (1988) 256.

- “ Le macédonien “, Langues indo-européennes (Paris 1994) 206-220.

R. A. Crossland, "The Language of the Macedonians", Cambridge Ancient History III, 1 (1982) 843-47.

L. Dubois, “ Une tablette de malédiction de Pella : s’agit-il du premier texte macédonien ? “, REG 108 (1995) 190-97.

M. B. Hatzopoulos, “ Artémis, Digaia Blaganitis en Macédoine “, BCH 111 (1987) 398-412.

- “ Le macédonien : nouvelles données et théories nouvelles “, Ἀρχαία Μακεδονία VI (Thessalonique 1999) 225-39.

- “ L’histoire par les noms in Macedonia “, Greek Personal Names. Proceedings of the British Academy 104 (2000) 115-17.

- “La position dialectale du macédonien à la lumière des découvertes épigraphiques récentes“, (J. Hagnal ed.) Die altgriechischen Dialekte. Wesen und Werden (Innsbruck 2007) 157-76.

O. Hoffmann, Die Makedonen. Ihre Sprache und ihr Volkstum (Göttingen 1906).

J. N. Kalléris, Les anciens Macédoniens, v. I-II (Athens 1954-1976).

O. Masson, “ Macedonian Language “, The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Oxford-New York 1996) 905-906.

- “ Noms macédoniens “, ZPE 123 (1998) 117-20.

Em. Voutiras, Διονυσοφῶντοςγάμοι (Amsterdam 1998) 20-34.